A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston

A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston

A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston (PGFLB) documents the “erasure” of indigenous peoples in and around Boston, Massachusetts. Focusing on the built environment, the project highlights narratives of extinction—both overt and subtle—that are inscribed in the urban landscape. Although the city is imbued with settler colonial stories and symbols, and despite the fact that Native Americans were actually banned within the city limits until 2004 when the 329-year-old Indian Imprisonment Act of 1675 was formally repealed, Boston remains a Native place.

The project is inspired by historian Jean O’Brien’s book, Firsting and Lasting: Writing Indians Out of Existence in New England, which seeks “to understand how non-Indians in southern New England convinced themselves that Indians there had become extinct even though they remained as Indian peoples—and do so to this day” (xii). Focusing on local history writing in southern New England, O’Brien carefully examines over 600 histories of small towns and cities in Connecticut, Massachusetts, and Rhode Island written between 1820-1880 and identifies three recurring narrative strategies used to literally write Indians out of existence. She labels these enduring ideological constructs: firsting, replacing, and lasting, and demonstrates how together they contribute to the larger settler colonial project of elimination while continuing to negatively shape expectations about indigenous peoples today. O’Brien also shows us how symbolic erasure goes hand-in-hand with physical erasure. If (seemingly innocuous) local histories “performed the cultural work of seizing Indian homelands” (102), they also enabled and justified the political work and, more importantly, the physically violent work of dispossession.

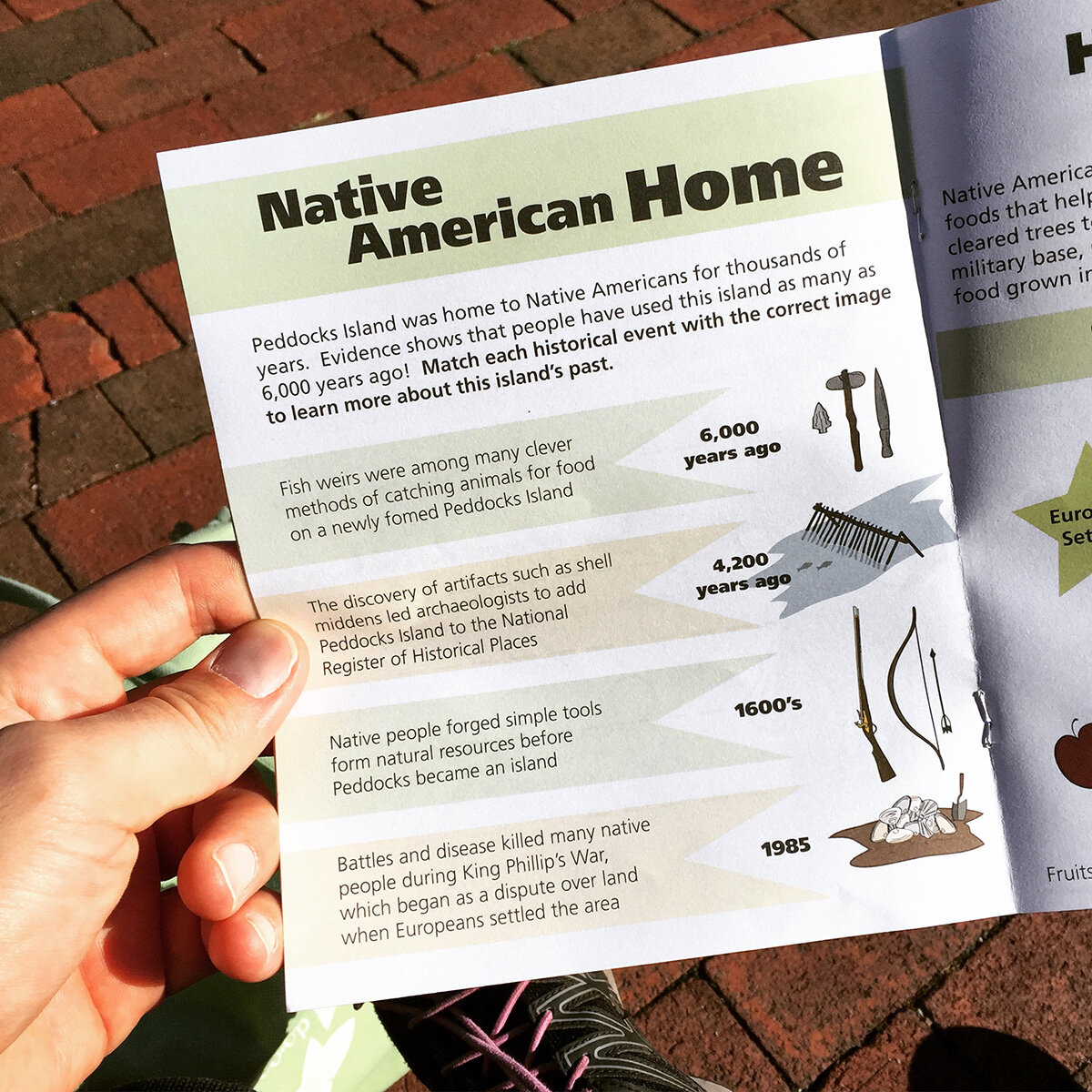

Processes of firsting, replacing, and lasting are not unique to southern New England, nor are they confined to local histories. These constructs, O’Brien argues, “can be found everywhere—in tourist sites and public history venues, and in news stories of all sorts” (xiv). O’Brien also notes that replacement narratives can be found in “historical monuments and commemoration, relics and ruins, place-names, and in the land itself” (56). These observations serve as prompts for A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston, which highlights examples of firsting and lasting in the built environment, including tourist sites, public history venues, historical monuments, and place-names throughout the metropolitan area. PGFLB demonstrates that the “master narrative of Indian extinction” persists in part because of its spatialization. The narrative is embedded in the landscape. And its persuasiveness is a result of the fact that we encounter messages of extinction on a daily basis in historical monuments and street names. “Settler common sense” is not just performed by the historical reenactors who seem to occupy every street corner in downtown Boston, but is projected through the built environment itself.

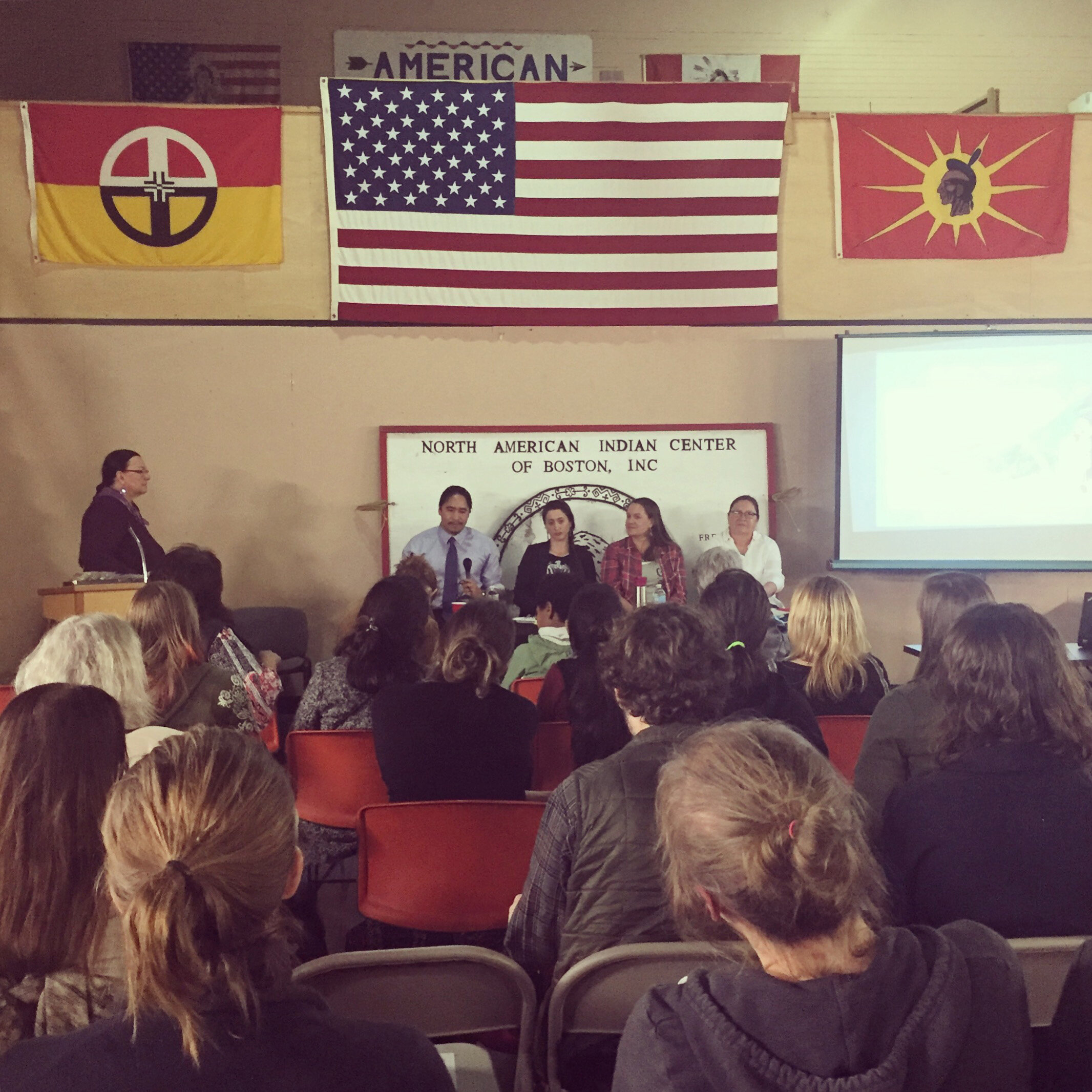

A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston seeks to disrupt that common sense. Like O’Brien’s book, PGFLB is also about resistance to erasure in the past and present. Thus it points to contemporary struggles throughout Native New England and highlights organizations like the North American Indian Center of Boston, initiatives such as the Wôpanâak Language Reclamation Project, and resources like the radio show Indigenous Politics: From Native New England and Beyond.

We encourage you to read O’Brien’s book and listen to her interview on Indigenous Politics. Most importantly, we welcome your contributions to A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston. As a growing archive, the success of the project depends on your participation. Help us document examples of firsting and lasting in and around Boston. Please email your contributions to firstinglastingboston@gmail.com or add the hashtag #firstinglastingboston to your photographs.

Definitions

What the heck is firsting and lasting? The definitions are both straightforward and complex. Often the processes of firsting, replacing, and lasting overlap, such that a single text or monument might participate in all three simultaneously.

First Encounter Beach, Samoset Road, Eastham, MA

Firsting

Firsting involves claiming to be the first one to do something that’s already been done. It’s similar to “discovering” a place that’s already inhabited. Christopher Columbus’s so-called “discovery” of America is a great example of firsting, and the term Columbusing, which became an internet meme in 2014, comments on the absurdity of this form of discovery while also highlighting the persistence of its logic.

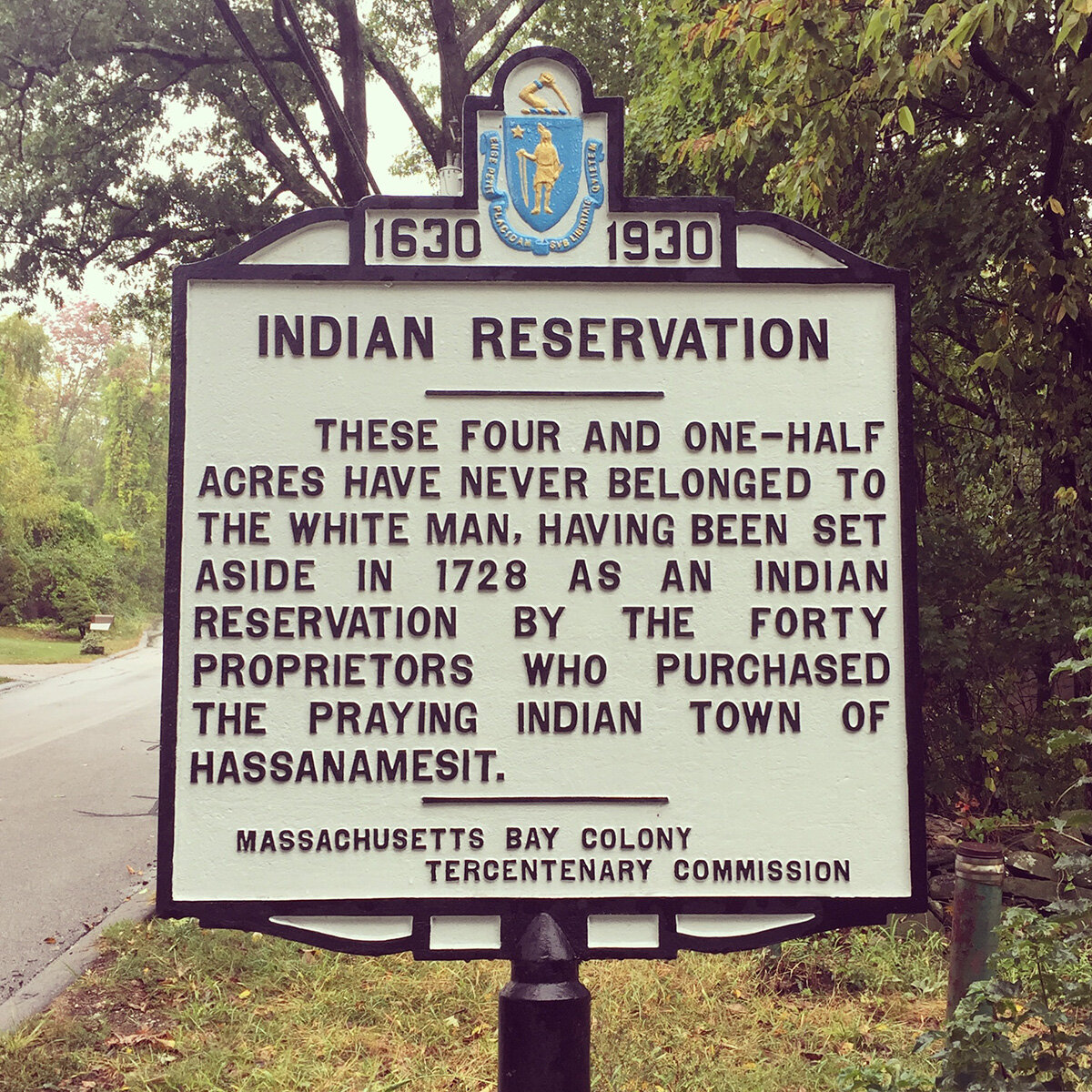

Firsting can also be understood as the creation of origin stories that conveniently overlook and are thus purified of competing narratives. 1630, a date inscribed on monuments, signs, and buildings throughout Boston, encapsulates the city’s origin story. Technically, Boston was founded in 1630, however, this place has a much deeper and richer history. Many settler origin stories do acknowledge indigenous peoples, however, they are incorporated only as a preface for non-indigenous history. Indigenous peoples are literally relegated to the preface or first chapter of the story, just as they are relegated to the past and denied contemporary and future presence. The fabrication of origin stories and places, like Plymouth, are an essential ingredient in the settler colonial project of elimination.

Firsting often establishes a hierarchy. According to O’Brien, firsting is an assertion “that non-Indians were the first people to erect the proper institutions of a social order worthy of notice” (xii). Similarly, she also defines it as a “scripting choice that subtly argues for the sole legitimacy of New English ways” (6). Non-Indian modernity is the flipside of Indian extinction. Indeed, settler modernity is produced in part by eliminating Indians from the landscape. “The end product of firsting,” O’Brien argues, “is the successful mounting of the argument that Indian peoples and their cultures represented an ‘inauthentic’ and prefatory history. The New England break with the traditional world of Indians (building upon their break with feudal Europe) made possible the insidious claim that New England erected the first houses, institutions, polities, and economies—the first social order—in the modern world” (52-53). In short, firsting is the oft-repeated claim that authentic history begins with European settlement.

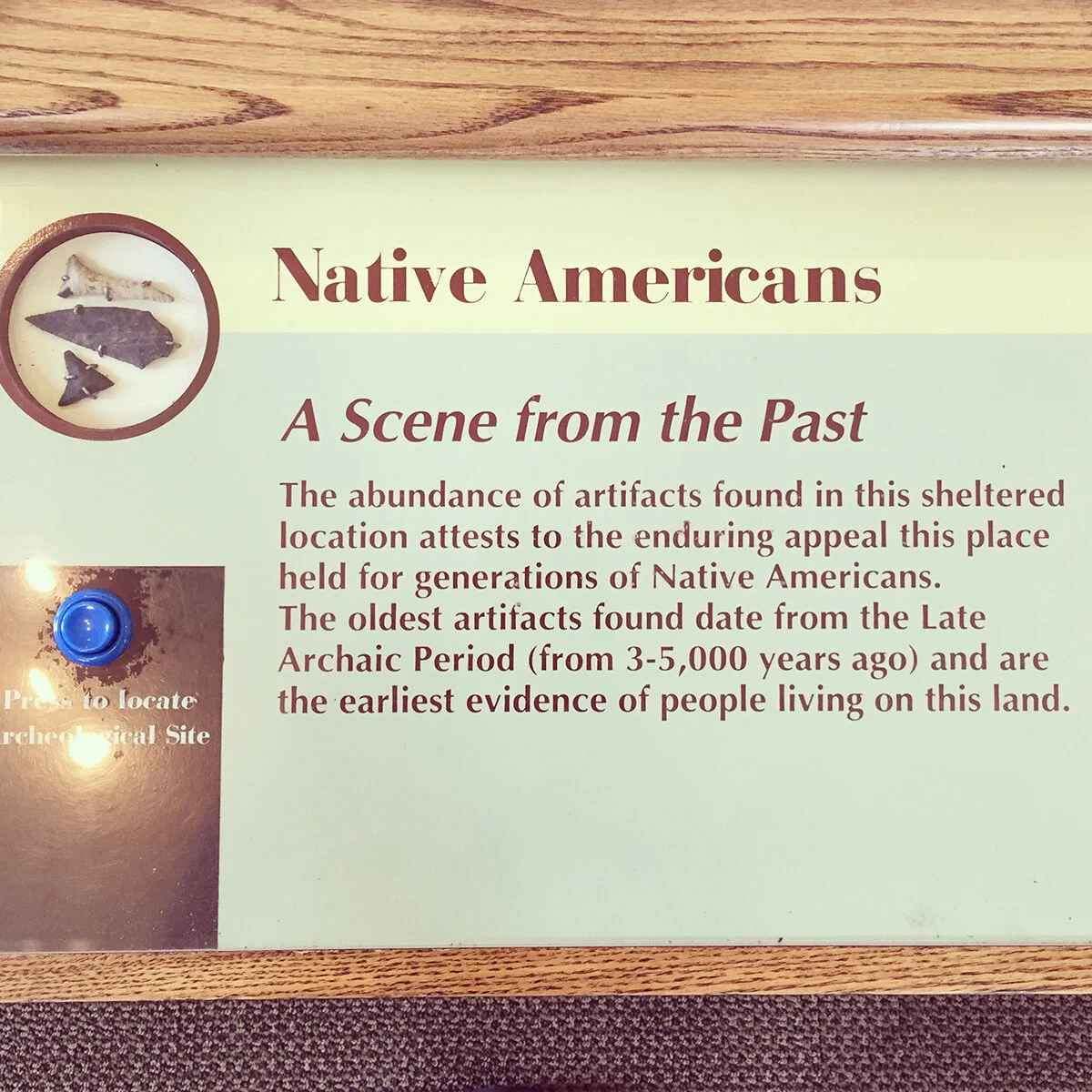

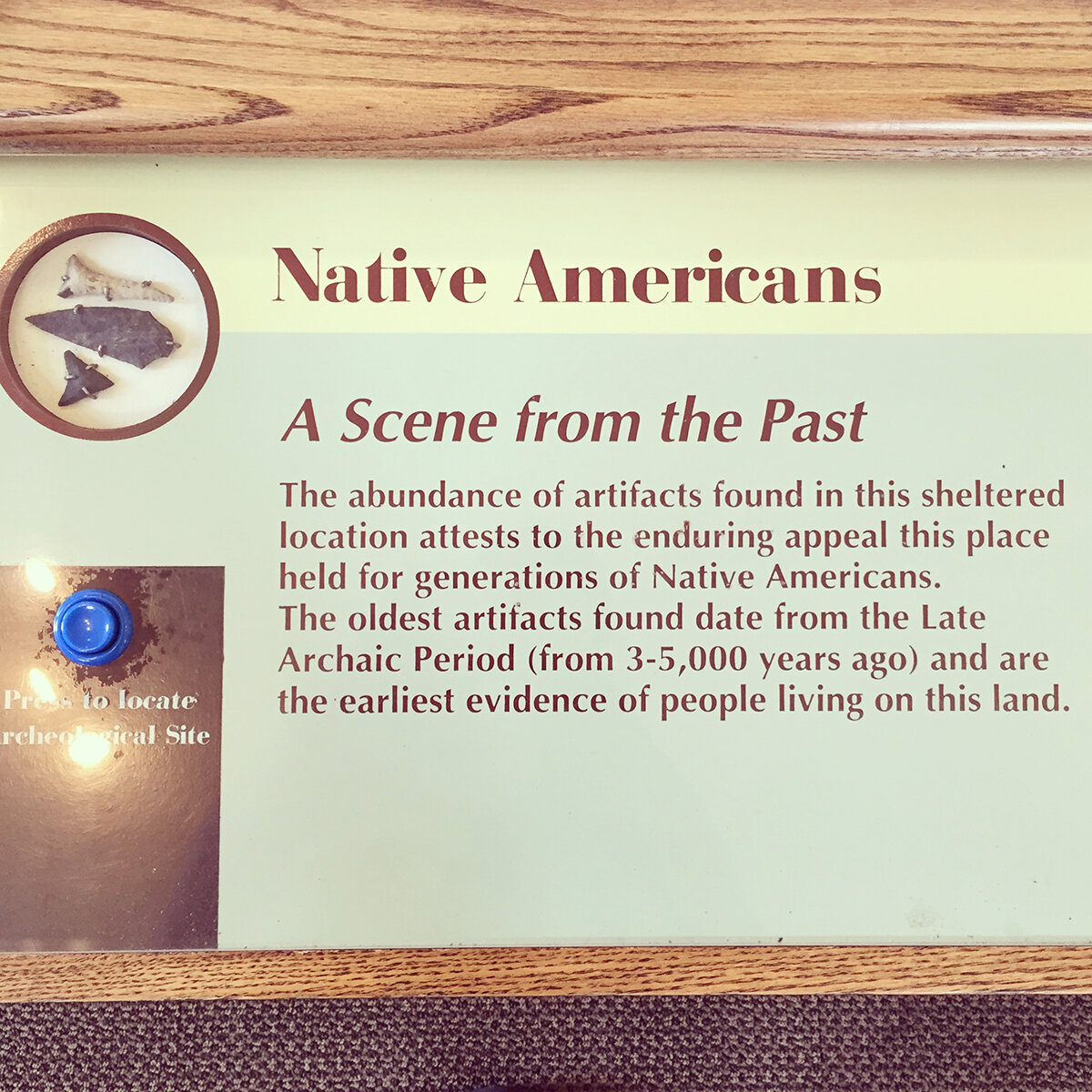

Interpretive display at the Arnold Arboretum Visitor Center

Lasting

Lasting is the opposite of firsting. It emphasizes Native lasts, as opposed to settler firsts. It often involves claiming that someone else is the last to do (or be) something that they continue doing (or being). Lasting insists on finality despite overwhelming evidence to the contrary. It insists that the last is really the last when in fact it is not. The power of lasting, therefore, lies in its capacity to persuade regardless of fact. O’Brien defines lasting as “a rhetorical strategy that asserts as a fact the claim that Indian can never be modern” (107). In other words, Indians are stuck in the past—characterized by cultural stasis and/or loss. In contrast, non-Indians propel history forward through a combination of adaptability and ingenuity. “Indians reside in an ahistorical temporality,” writes O’Brien, “in which they can only be the victims of change, not active subjects in the making of change” (105). Cultural dynamism is a privilege of whiteness that affords an exclusive claim on progress.

Lasting may be more easily defined or grasped through example. The Last of the Mohicans. You’re probably familiar with this phrase. Perhaps you’ve seen the 1992 film starring Daniel Day-Lewis. Maybe you’ve even read James Fenimore Cooper’s 1826 novel on which the film is based. Regardless, the phrase evokes death. It’s synonymous with extinction. No additional context is required to grasp this fundamental message. Lasting draws on and reproduces the myth of the vanishing Indian and the dying race.

“Squanto was the first last Indian,” O’Brien notes, “but he was decidedly not the last” (108). There are many famous last Indians—some are historical, others fictional; some are individuals like Ishi, others are groups like the Mohicans. Lasting can also be applied to events, such as the so-called Indian wars. The Black Hawk War of 1832, for example, is commonly depicted as “the last Indian war east of the Mississippi River.” Last Indians—famous or otherwise—are often found in unexpected places. Their names are frequently inscribed on the land itself; used to organize the territory in a way that amplifies the message of extinction. You are just as likely to encounter a last Indian in a quiet suburban neighborhood as you are in a historical text or Hollywood film. The name Squanto, “last of the Patuxet,” animates the landscape of Greater Boston, particularly around Quincy. You can drive on East Squantum Street to Squantum Elementary School, Squantum Marsh, and Squantum Point Park. Or you can sail from the Squantum Yacht Club through Squantum Channel. O’Brien refers to lasting as the “last of the [blank] syndrome” (xxiv). Like firsting, there is an endless list of possible lasts, all of which gesture toward extinction. As settlers, we have an open invitation to fill in the blank.

The narrative construct of Indian extinction—or lasting—is often located, O’Brien observes, in the complex discourse around “blood” and in stories about the “last full-blooded Indian” (107). The “last Indian” can often be read as shorthand for “last full-blooded Indian,” an idea that implies anything less than full-blood is not fully Indian. Like cultural dynamism, racial mixing is construed as a “privilege of whiteness” (107). Settlers are invigorated and improved through selective mixing, whereas for Indians it is always deadly—to mix is to assimilate and therefore to lose one’s claim to indigeneity. For non-Indians, the ability to mix fuels a “progress narrative,” whereas for Indians it underpins a “degeneracy narrative.” O’Brien frames lasting in terms of the “temporalities of race” and highlights a pervasive “degeneracy narrative” that supplements the broader “extinction narrative.” Blood, coupled with the idea of cultural stasis, O’Brien argues, “secured the mythology of Indian extinction” (119).

Massachusetts State Seal outside the Massachusetts State House in Boston

Replacing

Firsting and lasting are the most straightforward and familiar of the narrative strategies identified by O’Brien. As cradle of the American Revolution and home to one of the nation’s most beloved origin stories, Boston overflows with settler firsts and Native lasts. Replacing is a little more complex, but, like a good optional illusion, once you get it the first time, you’ll start seeing examples of replacing all around the city.

Replacing often functions as a bridge between firsting and lasting, linking the establishment of a new modern social order with the physical and imaginative replacement of Indians. Replacing also supplements firsting and lasting, which “alone did not finish the work of claiming Indian places” (55). Basically, settler colonialism is all about replacement. It’s what Patrick Wolfe means when he argues that “settlers come to stay.”

Although it takes many forms, replacing typically works through rupture and self-justification. First it establishes a rupture or break between an Indian past and a non-Indian present—maintaining the degeneracy and progress narratives as separate trajectories—and then it justifies the replacement of a supposedly inferior social order with a superior one. In the process, O’Brien argues, “non-Indians stake a claim to being native” (xv). This “seizure of indigeneity” is not about becoming Indian so much as becoming rightful owners of the land (53). Appropriating the category “indigenous,” it turns out, is an effective means of appropriating the land. In telling the story of how non-Indians eclipsed Indians, these narratives also reinforce the inevitability of replacement. There were no alternatives, we are told. Replacement was preordained. Local narrators, O’Brien writes, “formulated a history that negated previous Indian history as a ‘dead end’ (literally), supplanting it with a glorious New England history of just relations and property transactions rooted in American diplomacy that legitimated their claims to the land and the institutions they grounded there. In the process, they rationalized their history of settler colonialism and claimed New England as their own” (55).

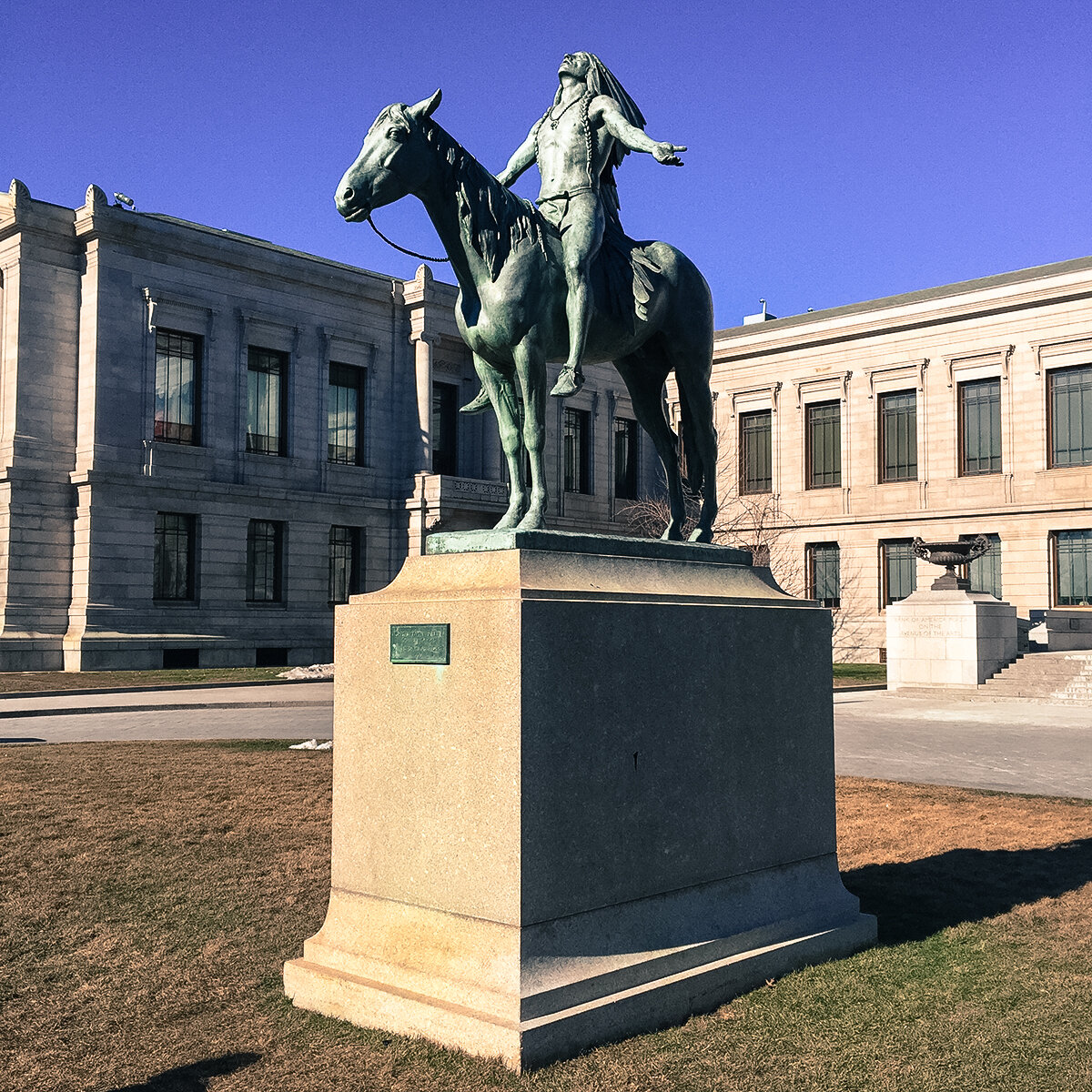

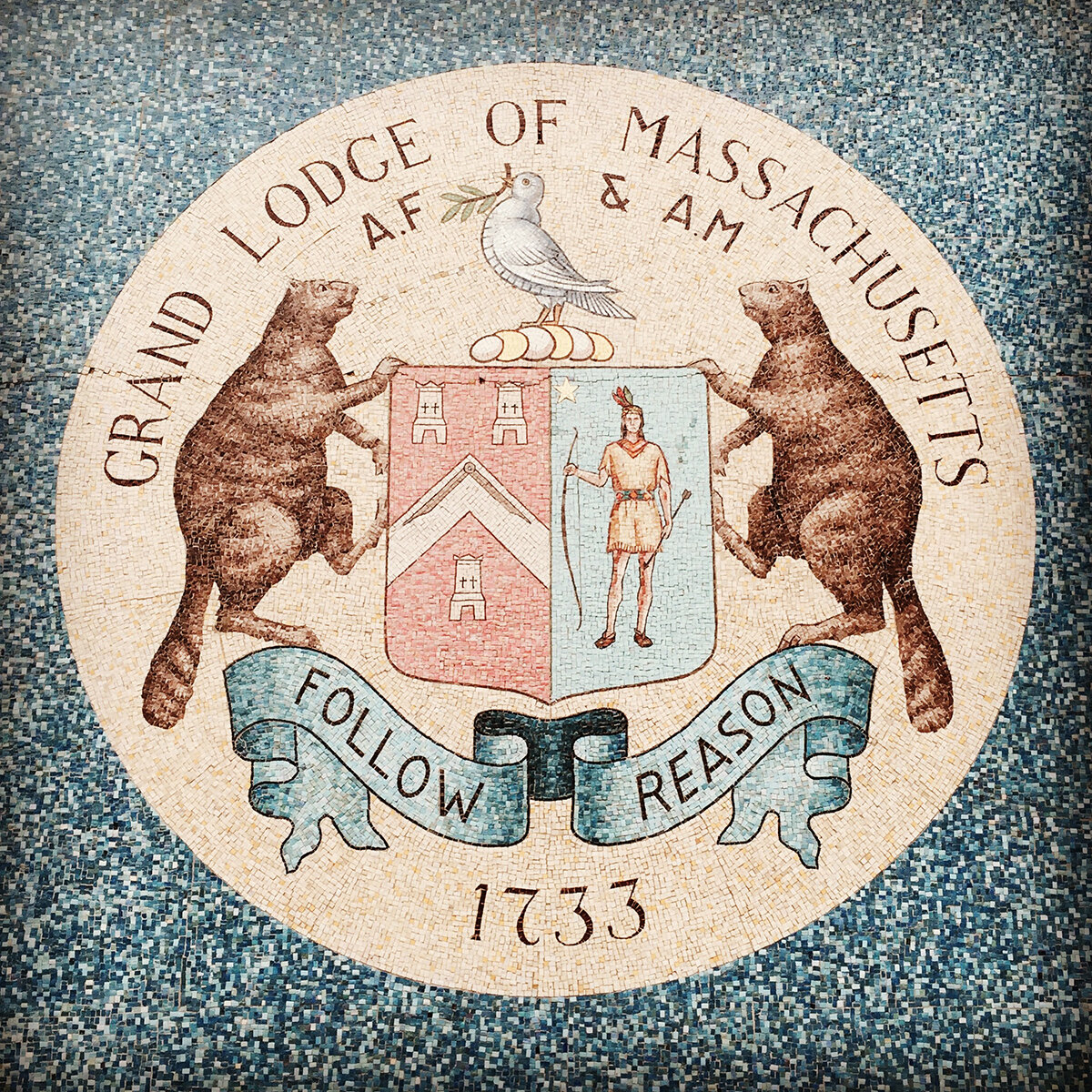

The message of replacement circulates through monuments, historical commemorations, place-names, archaeological sites, and ideas about landownership and property. Replacement narratives are of particular interest to A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston precisely because they are embedded in the built environment. Mundaneness combined with repetition is what gives the message of replacement its strength and durability. Monuments don’t have to be explicitly about colonization or Native Americans to reinforce the replacement narrative. In fact, the most powerful articulations of replacement are often the most indirect. The John Endecott monument, for example, tucked away on the east side of the Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, embodies and projects the idea of replacement far more than the famous Cyrus Dallin sculpture, Appeal to the Great Spirit, which is prominently located in front of the museum’s main entrance on Huntington Avenue. Dallin’s sculpture along with Paul Manship’s Indian Hunter sculpture on the museum’s north side are examples of lasting. Together the three Indian sculptures that flank the building implicate the Museum of Fine Arts in the ongoing project of settler colonialism.

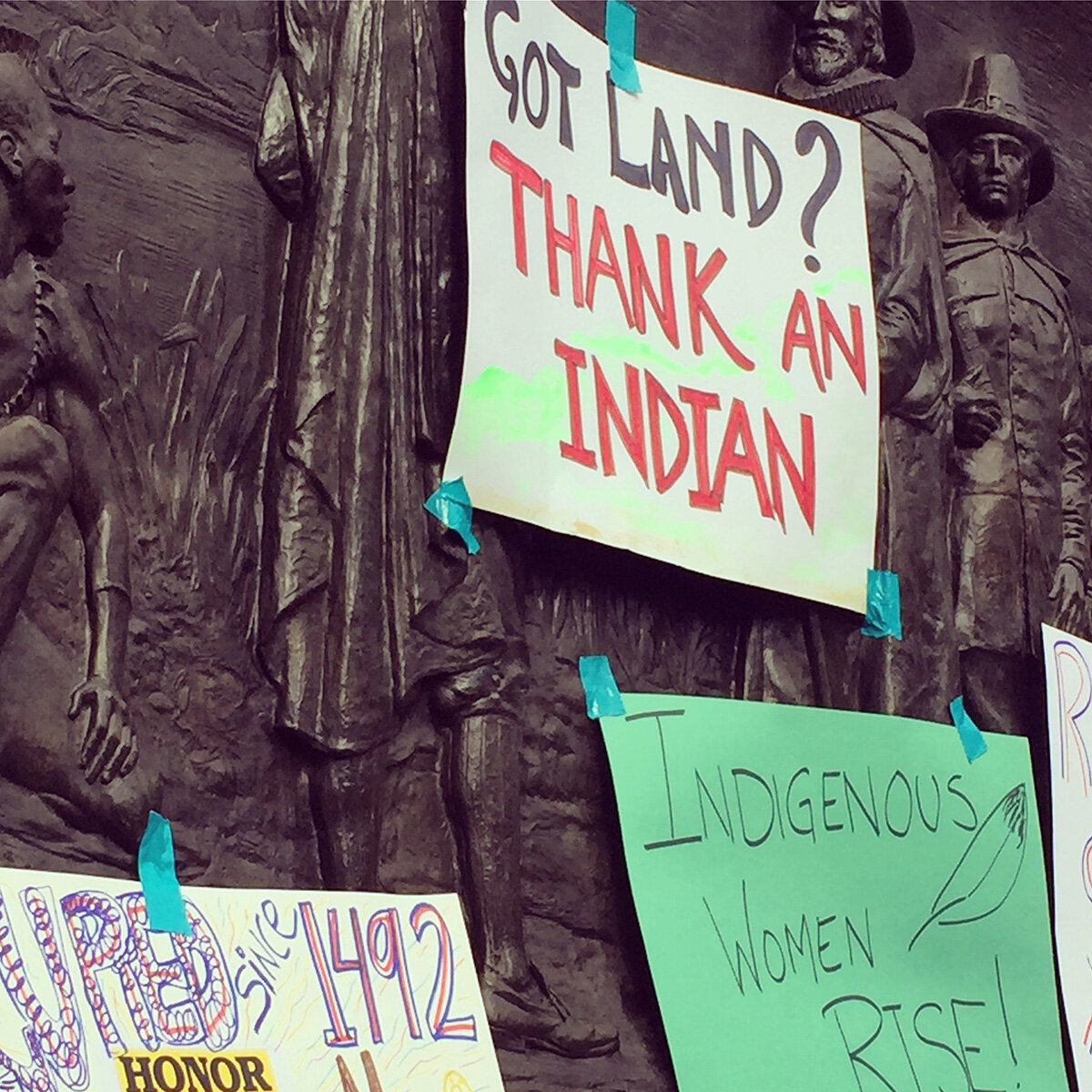

Mashpee Land Sovereignty Walk & Rally in October 2018

Resisting

Despite its pervasiveness and persuasiveness, the replacement narrative cannot overturn the simple fact that indigenous peoples have survived and continue to call New England home. O’Brien’s fourth category, resisting, is all about survival, adaptation, and the defense of land and identity—highlighting the peoples whose very existence ruptures the extinction narrative and refuses the replacement narrative.

Countering these widespread narratives, O’Brien documents numerous examples of resistance to settler colonialism, showing how “Indians resisted their effacement from New England in the nineteenth century by embracing change in order to make their way in a changing world, as they had done for centuries” (145). This form of resistance is personified, O’Brien suggests, by the Pequot minister, political theorist, and activist William Apess, especially his famous Eulogy of King Philip speech. Delivered in Boston in 1836 on the anniversary of the King Philip’s War of 1675-76, Eulogy challenged settler use of public memory and commemoration to erase native stories and peoples, and also linked New England Indian history to contemporary struggles for recognition and assertions of sovereignty. Throughout his lifetime Apess worked tirelessly to “reclaim indigeneity from non-Indians who attempted to seize it through the construct of modernity” and also to “reclaim New England as an Indian place” (189-90).

New England is full of settler firsts and Native lasts, and Boston is saturated with settler colonial stories and symbols, but the region and the city are also full of Native peoples and Native stories. Although A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston documents the “erasure” of indigenous peoples, it is ultimately about survival. It is about recognizing the ongoing presence of indigenous peoples in this place we now call Boston, and it is about reckoning with contemporary forms of colonization, including the tired narratives that prevent many of us from seeing how Boston was, is, and will always be a Native place.

Acknowledgements

Indebted first and foremost to Jean O’Brien, A People’s Guide to Firsting and Lasting in Boston draws inspiration from many other sources, including indigenous scholar-activists such as Mishuana Goeman, J. Kēhaulani Kauanui, Audra Simpson, and Eve Tuck, as well as critical cartography projects such as Mapping Indigenous LA (UCLA), Knowing the Land Beneath Our Feet (UBC), Ogimaa Makana (Gichi Kiiwenging/Tkaronto/Toronto), and Bdote Memory Map (Mnisota Makoce/Minnesota).