COMMON TENSIONS

Sarah Kanouse and Nicholas Brown, “Common Tensions,” Passepartout 22, no. 40 (2020), 183-208.

Special issue: New Infrastructures—Performative Infrastructures in the Art Field

ABSTRACT / Based in the hilly, unglaciated Driftless Area of the upper Midwest of theUnited States, Common/Place is a self-organized, off-the-grid platform for ecological resilience, cultural inquiry, and land-based pedagogy. The rustic. setting offers a space to examine how such rural spaces have been both produced by and mobilized within the linked projects of capitalist extraction and settler colonial extermination and to connect and grow the nodes of resistance always present within such systems. Our primary project up to this point has been a series of experimental seminars assembling artists, writers, and cultural workers to learn from and with naturalists, historians, farmers, citizens of the Indigenous Ho-Chunk Nation, and the land itself. This grounded creative research and pedagogy generates a network of informal relationships that connect the urban and rural to break through the present moment of political retrenchment and set the stage for social and ecological cooperation in the face of the climate chaos to come. This practice-based, epistolary essay reflects on the first four years of Common/Place, highlighting constitutive tensions and continued negotiations around property, relationships, ecology, and time—individual, generational, and geological—that can quickly become sedimented in infrastructure and no longer open to question.

The Politics of Place Attachment (excerpt)

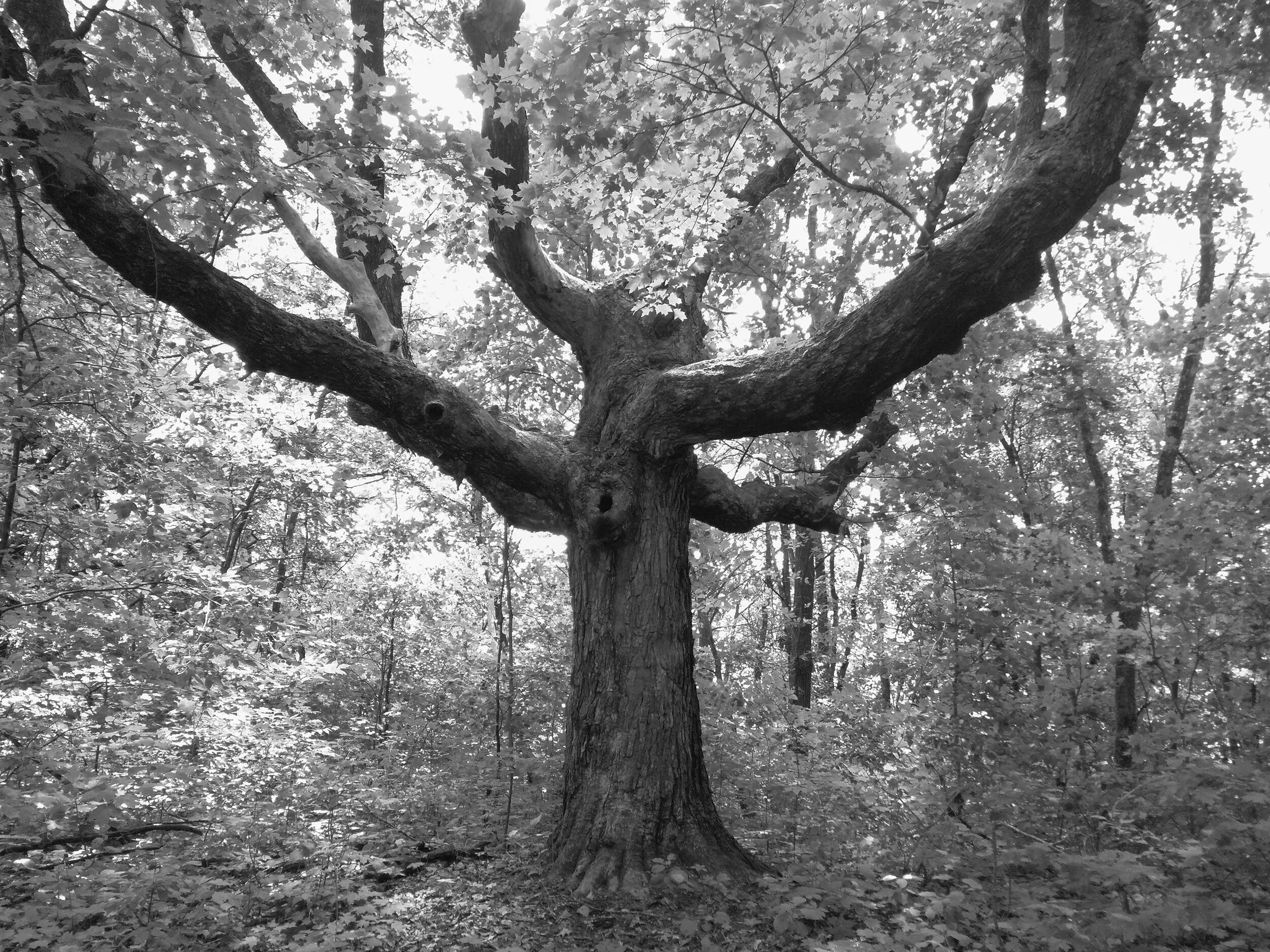

I’ve been coming to this place since I was 4 years old. That is now more than 40 years. The white pine seedlings I planted as a kid with my dad have grown into big trees, over fifty feet tall in some cases.

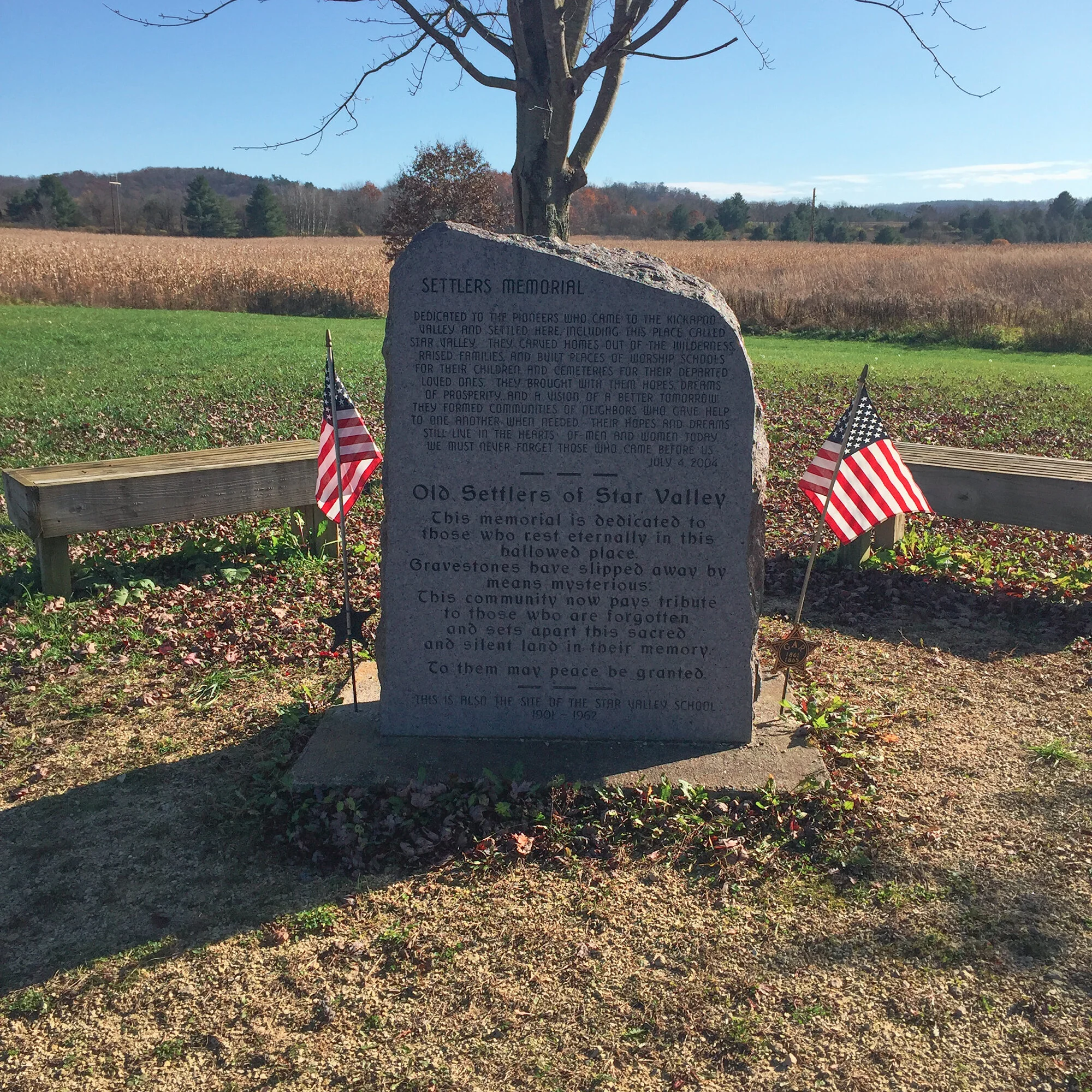

Measured against my own lifetime, my connection to this place is as deep as it gets. Measured against the three, four, or even five generations of the prideful settler, my connection grows shallower. And measured against the hundreds of generations the Ho-Chunk and other indigenous peoples have called this place home, my connection dissipates to the point of nothingness.

I am constantly aware of the relativity of my attachment—of my permanent status as a newcomer and an outsider. But I keep coming back—even though I now live more than 1200 miles away.

Despite the inconvenience, I resist the temptation to exchange this piece of land for another one. I resist the fungibility of land as commodity, even if the distance often causes exasperation and complicates logistics. The relationships and obligations I feel are not transferable, nor are they things I can simply walk away from. Reflecting on the impossibility of detachment from settler colonial homelands, scholar-activist Shiri Pasternak writes: “my love for these places is constitutive of my identity, violence and all, and to disavow them is to choke off the attachments that give our lives their rich and challenging meanings and form the anchors that tether our responsibilities” (Pasternak, 2017, p. xxvi).

I am keenly aware of the complicity of my attachment—how my attachment is part of that “violence and all.”

Writer KT Thompson’s query about love of place rings in my head, spurring other questions: “I wonder if when settlers write of their attachments to place, of the five generations that have lived and cultivated the land, they express a form of love at the expense of another, where ‘love’ equals property and inheritance” (Thompson, n.d.). Is it possible, I ask myself, to honor these different and incommensurable scales of place attachment? To recognize the substantive depth of place-knowledge gleaned over thousands of years? To resist the impulse to become native to place? To resist seizing indigeneity, and focus instead on abolishing white possessiveness and relationality as a means of deepening settler place attachment?

Continue reading Common Tensions