Over the Levee, Under the Plow / A Mobile Seminar

Anthropocene Drift - Field Station 2 / Mississippi: An Anthropocene River

September 25-29, 2019

Blackhawk Park, De Soto WI — Black Hawk State Historic Site, Rock Island IL

Blackhawk Park is Indigenous Land - Beyond Acknowledgement

Reflections on “Over the Levee, Under the Plow”

Nicholas Brown, Ryan Griffis, Sarah Kanouse

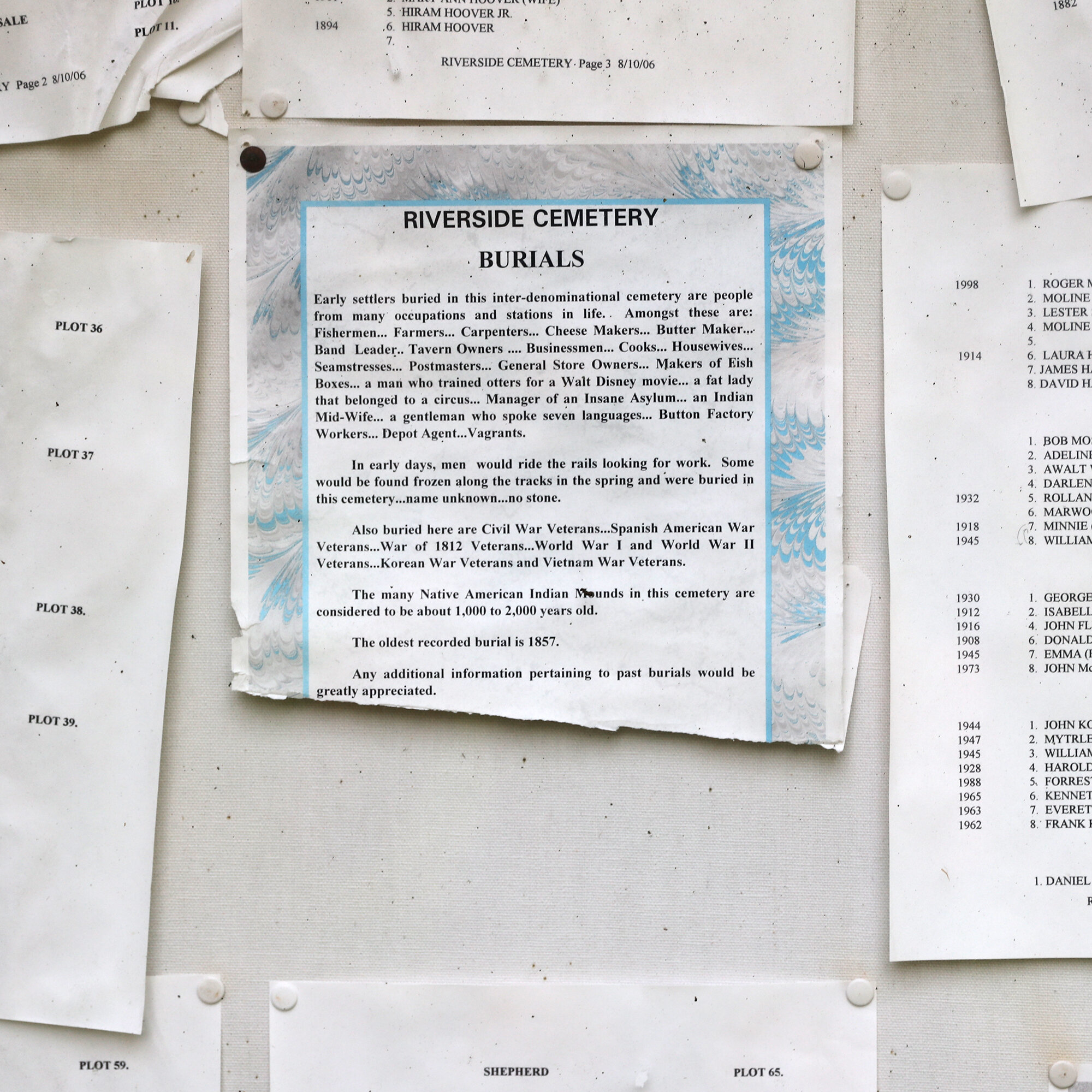

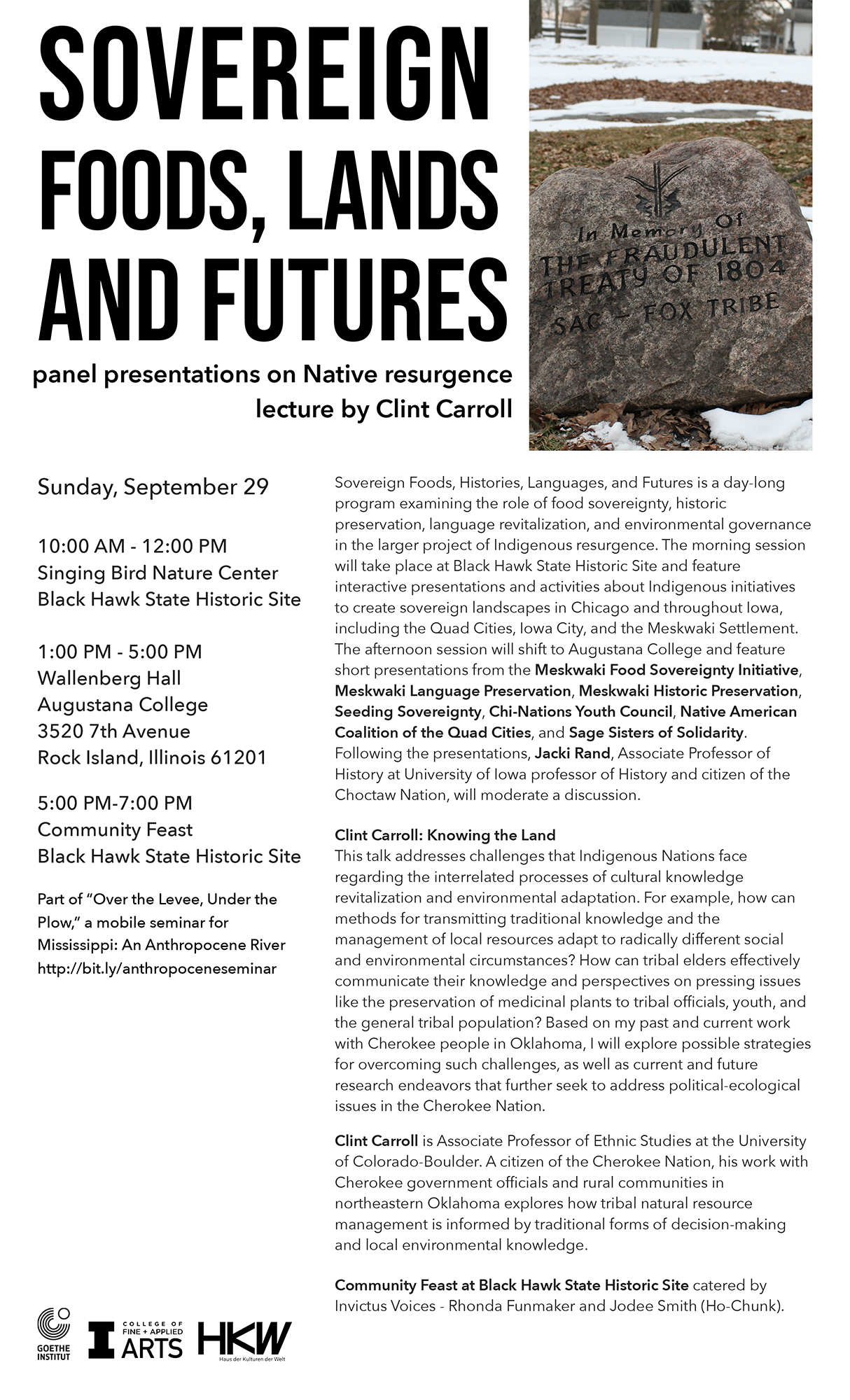

Arriving in cars, vans, pick-ups, and canoes, a group slowly assembled under an overcast sky on the banks of the Mississippi in a place called Blackhawk Park, near the small town of DeSoto, Wisconsin. As organizers of the convocation for Anthropocene Drift (Field Station 2), we believed it was necessary to acknowledge that we were gathering on Indigenous land. On Ho-Chunk land. However, we chose not to begin our program, “Over the Levee, Under the Plow,” with a formal land acknowledgement. Rather, we viewed the five-day seminar — itself building on eighteen months of focused research and planning — as a prolonged land acknowledgement, and also a concerted attempt to move beyond acknowledgement. We need to move from words to actions, in other words, as we grapple with what it means to live and work on Indigenous land, on Ho-Chunk land.

Land acknowledgements are necessary but insufficient gestures of accountability to Indigenous peoples and places in the colonial present. Chelsea Vowel, a Métis writer and teacher from Alberta, invites us “to start imagining a constellation of relationships that must be entered into beyond territorial [or land] acknowledgments.” She encourages us to “start learning about [our] obligations as a guest in this territory.” One of the very first obligations as guests is to know the names of your hosts, and to listen closely to them. In this case, doing so elevates homelands and places of belonging instead of field stations, a perspectival shift suggested by Ojibwe artist Andrea Carlson.

“Moving beyond territorial acknowledgments,” Vowell continues, “means asking hard questions about what needs to be done once we’re aware of Indigenous presence. It requires that we remain uncomfortable, and it means making concrete, disruptive change.” Acknowledgement is therefore not an end itself but a provocation to disrupt, to “unsettle” — figuratively and literally — our relationships to the land, to history, and to one another. As three white settlers, artists, and academics, we welcomed participants to lands that are not rightfully ours and spoke with voices authorized and amplified by white supremacy. Ours is the white, middle-class subjectivity — already a complicated assemblage of varying identities — described by anthropologist Heather Anne Swanson as “predicated on not noticing… on structural blindness: on a refusal to acknowledge the histories we inherit.” So we began by unsettling the very land on which we gathered — acknowledging our own complicity in the violence that secured our place there.